It is the wood that is burned inside the wooden milking containers the lmala, that imparts a large part of the taste and aroma of Samburu smoke cured fermented milk. The first time I tasted Samburu milk was in the Spring of 1994. I arrived on “Babies Coach” which was a bus body welded onto the chassis of an extra heavy long distance truck. Even so, the drive over the then rough road from Isiolo to Wamba to many hours. I was on the roof along with luggage, a few murran, warriors in traditional dress, as styles change, and this was a long time ago, and as it was all so new to me I can just say, they will have had a fabulous hair style, and many articles of beaded ornamentation, a rongu, which is a small club, sometimes made from the root of a tree that ends in knob, but can also be construed and ornamented with bead work — which is the more common style. At that time they also always carried spears. These have long since been replaced by AK 47s. The murran closest to me took care of me. He told me when to duck so I as not cut up by the thorns of acacia trees under whose branches we sometimes passed under. I recall this ride on the top of Babies Coach as one of joyful life moments. I was alone. I was getting myself to what for me was a remote place, and as it happened, I saw three double rainbows over the Mathews Range which rise to the fight of the road once one passes through Archers Post.

I arrived in the evening. Dark falls quickly on the equator. It was walking by the light of the full moon in what is now the Tree Top area of Wamba, now a part of the town, but then it was still bush. My friend took me to her mother’s house. Following him, I crouched and moved sideways through the door into his mother’s hut — a round house made of sticks and cow dung, roughly 12 feet, or 4 meters in diameter. No windows, just that door, and a fire smoldering on the floor between three rocks. That was the kitchen. Once we were settled in, she passed around milk in a cup — the leather cap from a lmala. At that time, people living in traditional houses had no artificial illumination of any kind. No candle, no kerosene light, no flashlight. At that time, flashlights were a luxury, with the gift of one being hughely appointed. But, I digress.

It was dark inside this hut. The moonlight did not penetrate, and the fire was not a flame fire. It was the smoldering tips of three sticks which were how wood was and and still are burned in a three-rock kitchen stove. If you have not seen this the of cooking device, then imagine three rocks of equal size set at a distance from each other so that they can support an aluminum kettle or an aluminum handleless pot used for making tea, or boiling water for ugali, which is polenta made with white corn, or at that time, if the woman was beginning to experiment with potatoes, or pasta, new foods in the region for families who lived as pastoralists. I still digress! A woman told me a few years later, on a return trip, that there as pressure from the children who were fed at school to offer a more varied diet. No matter where we live, no matter the culture we are born into, we all love our children, and will do whatever we can to make them happy.

Back to that milk. I had just arrived on Babies Coach. And now, here I was, sitting in this dark hut and the air smokey. Without light, I couldn’t even see all of the other people who were there as their complexions absorbed whatever stray light might have come in. So, it was in darkness, that a cup of milk was handed to me. And in darkness that I tasted one of the more fabulous tastes of my life.

As of this writing, this was twenty-nine years ago. Before this trip I had read in a peer review journal that the staple food of the Samburu was “milk.” At the first sip I realized that this “milk” had nothing to do with milk as I knew it. To call this milk was to call wine grape juice. The milk was slightly thickened, tasted like vanilla ice cream, and was suffused by an ineffable smokiness. For the few anthropologists who have mentioned anything about the Samburu milk, they mostly just referred to its smoky flavor. We, from the outside, read “smokey” but they read through to the burning botanical with which the container was cleaned. Like a smoked meat connoisseur who tastes through to the wood used — “Ah, he or she says, apple wood, lovely!”

And that is how my quest began to learn about Samburu milk. This became a thirty-year project to learn how to make that milk, and to document it with such specificity that Samburu who are no longer living in stick and dung huts could make a stab at creating it. In this I was inspired by Marcel Maget’s work on the rye bread baked once per year in the alpine village of Vilar d’Arene. His meticulous work, ‘Le pain anniversaire à Villard d’Arène en Oisans Broché” was researched and written over roughly thirty years beginning in 1948. The village had been baking their rye bread once per year, each family baking one batch of rye bread in an enormous wood fired oven. This is because the village is at the tree line so gathering enough firewood for the oven is not easy. When the road up from Grenoble finally became passable in the winter they stopped baking this annual bread as they could now purchase bread in a shop. But, when Maget finally published in the 1970s the villagers read the book and revived the practice as a village celebration of their history. I am hoping that this work on Samburu milk will do the same for them.

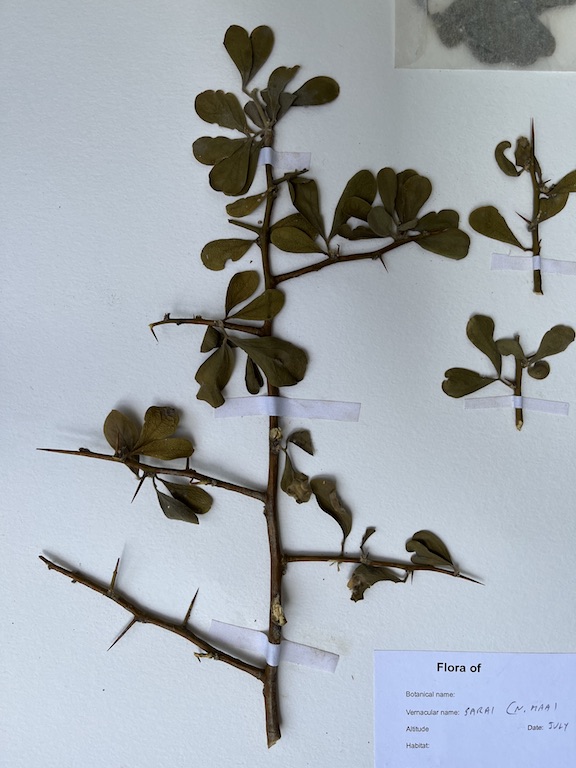

The botanicals used are

The artistry of the woman who prepared the lmala for milk is able to make the most of the flavor tonalities of each wood, or not, depending in her skill. I have fully documented the preparation of the lmala to provide the full context for the ethnobotany.

When milk was plentiful, women selected the botanicals she burned based on the keeping qualities the wood brought to the fermentation process. When milk was abundant, wood was selected that would preserve the milk the longest. Now, when there is rarely cow milk available, women are selecting primary for taste and aroma.

There are many woods to choose from, and so what woods a Samburu woman uses does depend on where she lives — Lowlands choices are different form Highland choices, and choices differ within these broad geographic areas depending on exact elevation and where one is in relationship to mountains, washes, and other features that might favor one plant over another.

Highly sought after woods that grow in the mountains are collected by large groups of women as there is security from wild buffalo and elephants when moving in a group.